Famous for Maoshan Taoists, High-Quality Herbs for Dampness and Spleen Strengthening

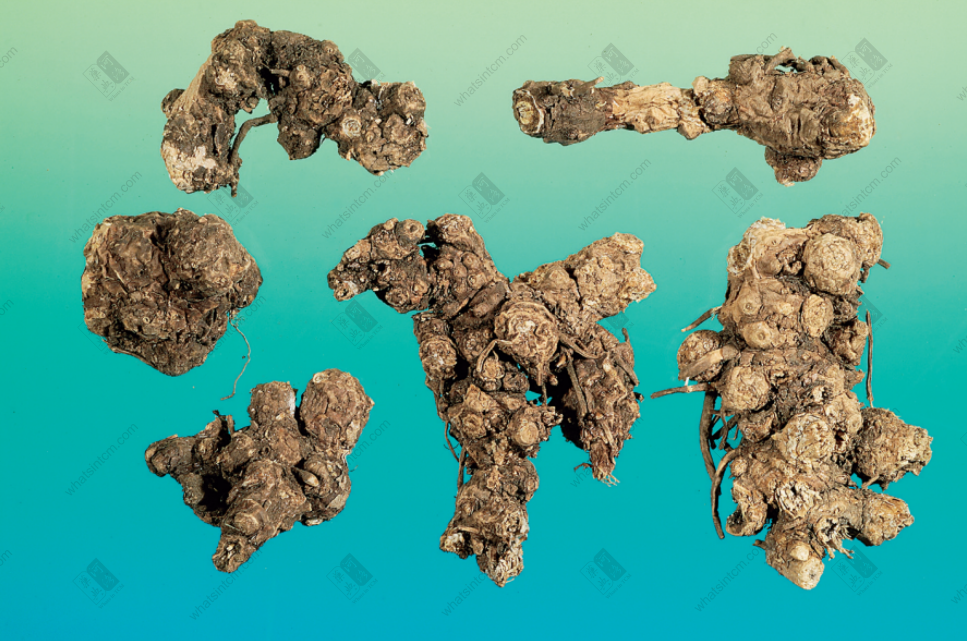

Northern Cangzhu: Nodular cylindrical, with a dark brown surface.

Northern Cangzhu: Nodular cylindrical, with a dark brown surface.

Northern Cangzhu.

Northern Cangzhu.

Southern Cangzhu: Beaded, jointed, curved, grayish-brown.

Southern Cangzhu: Beaded, jointed, curved, grayish-brown.

Maoshan Cangzhu: Easily broken, grows white mold and frost when stored.

Maoshan Cangzhu: Easily broken, grows white mold and frost when stored.

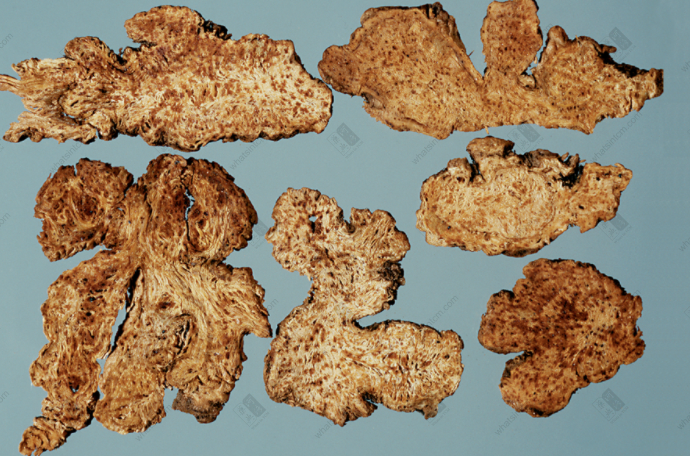

Sliced Cangzhu.

Sliced Cangzhu.

Sliced Cangzhu processed with rice-washing water.

Sliced Cangzhu processed with rice-washing water.

Distinct cinnabar spots visible on sliced Cangzhu.

Distinct cinnabar spots visible on sliced Cangzhu.

“Cangzhu in the furnace mixes with smoke from Jing, roasted together, smoke billows high. If only bats could fill the sky, to eliminate toxic tribes and bring peace to the people.”

“Song of Driving Away Mosquitoes” by Pu Songling, Ming Dynasty

The poem indicates that ancient people used Cangzhu to repel mosquitoes. The last two lines suggest using bats to eat mosquitoes, perhaps explaining why bats, besides their auspicious homophony, are another lucky symbol in the East.

According to the Fourth Edition of the Taiwan Pharmacopoeia, Cangzhu (https://whatsintcm.com/dt_articles/%e8%92%bc%e6%9c%ae/) is the dried rhizome of the Asteraceae plants *Atractylodes chinensis* (DC.) Koidz. or *Atractylodes lancea* (Thunb.) DC. Typically, depending on the place of origin, commercial products are divided into Southern Cangzhu and Northern Cangzhu. Southern Cangzhu is mainly produced in Jiangsu, Hubei, Henan, and other regions. That produced in Maoshan, Jurong County, Jiangsu Province, is specifically called “Maoshan Cangzhu.” It is of better quality and the most famous. Northern Cangzhu is mainly distributed in North China, Northwest China, Northeast China, and other areas. Due to climatic conditions, it is not easily cultivated in Taiwan, and it is also known by other names such as Xian Zhu, Jing Cang Zhu, Chi Zhu, Shan Ji, Shan Jing, Shan Ci Er Cai, and Qiang Tou Cai. The rhizomes are usually harvested in spring and autumn, cleaned of attached soil, sun-dried, de-fibered, sliced, and stored for use. The original name of this product was “Zhu.” Early herbal texts from the Han and Wei dynasties and before did not distinguish between Cangzhu and Baizhu. Its name first appeared in the book “Erya.” By the Northern and Southern Dynasties, Tao Hongjing’s “Ben Cao Jing Ji Zhu” recorded: “There are two types of Zhu: Baizhu has large, hairy, branched leaves and a sweet, less oily root, suitable for making pills and powders; Chizhu has fine, unbranched leaves, small roots, is bitter and oily, suitable for decoctions.” This marked the distinction between the two. Zhang Yuansu’s “Zhen Zhu Nang” from the Song Dynasty stated: “Chizhu can strengthen the stomach and calm the spleen, and it is essential for eliminating dampness and swelling.” This highlights its significant efficacy in drying dampness.

Maoshan Cangzhu is primarily produced in Maoshan. It generally presents as irregularly beaded or nodular cylindrical shapes, with a grayish-brown surface. It is firm and easily broken, with a mostly flat fracture surface and a distinctive aroma. The processed medicinal slices typically have a grayish-white cut surface with a grayish-brown periphery. Larger specimens, firm texture, cinnabar spots on the fractured surface, and a rich aroma are considered superior. The so-called cinnabar spots are small, scattered dots on the cut surface that resemble cinnabar, mainly formed by oil cavities and their secretions, serving as an important basis for identifying the quality of Cangzhu. If Cangzhu medicinal material is stored for a long time, fine white needle-like crystals may appear, known as “frosting.” This is primarily a mixture of atracenone and β-elemenone. Because of its white, hair-like appearance, it is also called “white mold.” This characteristic is rarely seen in the market today.

Northern Cangzhu’s rhizome is mainly nodular cylindrical, and individual pieces are usually larger than Southern Cangzhu. The outer surface is predominantly dark brown, turning yellowish-brown after the skin is removed. Compared to Maoshan Cangzhu, it is lighter in weight and has a looser texture. The fractured surface is light yellowish-white with scattered yellowish-brown oil dots. Generally, it does not form white needle-like crystals during storage, and its aroma is milder than that of Southern Cangzhu.

Additionally, there is a commonly confused variety called Guan Cangzhu, also from the Asteraceae family. Its surface is deep green. It is lighter in texture, and the fractured surface is usually uneven and fibrous, with a peculiar odor. It is mainly used as Cangzhu in Northeast China, while in Japan, South Korea, and other countries, it is often used as Baizhu.

Different processing methods are employed depending on the clinical application. Common methods include stir-frying with bran, where the wok is heated over high heat, bran is evenly scattered, and when smoke appears, the cleaned Cangzhu slices are added and quickly stir-fried until the surface turns deep yellow. It is then removed, the burnt bran is sieved out, and it is cooled for use. Another method is charred Cangzhu, where Cangzhu slices are placed in a stir-frying container, heated over medium heat until brown, then a small amount of water is sprinkled, and it is stir-fried over low heat until dry, then removed and cooled, and碎屑 are sieved out. There is also processing with rice-washing water, where cleaned Cangzhu slices are evenly mixed with an appropriate amount of rice-washing water, allowed to soak until the water is absorbed, and then stir-fried over low heat until the surface turns yellow, after which it is removed and cooled.

Cangzhu is one of the commonly used traditional Chinese medicinal materials. It is frequently used to dry dampness and strengthen the spleen. The Pingwei San formula, which regulates qi and harmonizes the middle, heavily utilizes it. Therefore, the Taiwan Pharmacopoeia has detailed regulations for its limits on sulfur dioxide and heavy metals such as arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead, allowing the public to use it with confidence.

【Image provided by】Professor Chang Xian-che, “Atlas of Authentic Medicinal Materials” https://whatsintcm.com