Beware of Buying the Wrong Expensive Traditional Chinese Medicine ‘Calculus Bovis’

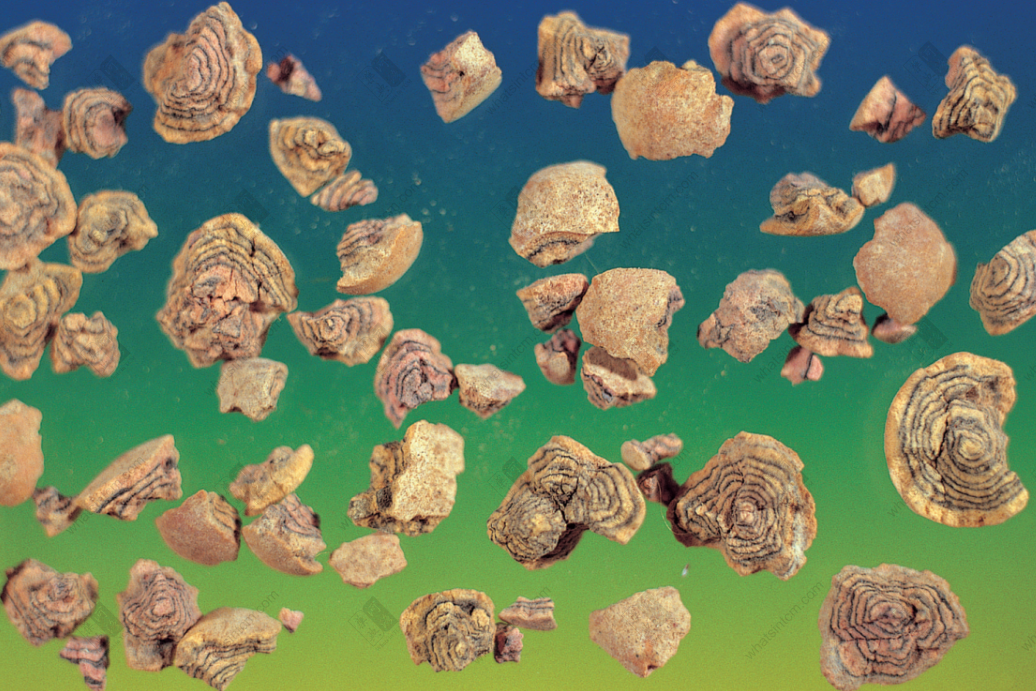

Jinshan Calculus Bovis: Oval, round, or triangular in shape, yellowish-brown in color, with a black, shiny thin film on the outer layer called ‘Wujinyi’ (black gold skin). The cross-section shows concentric ring patterns, layered and overlapping. It has a cooling sensation when tasted.

South American Calculus Bovis: Oblique cross-section shows white spots.

South American Calculus Bovis: Oblique cross-section shows white spots.

Argentinian Calculus Bovis

Argentinian Calculus Bovis

South African Calculus Bovis: Smooth and shiny exterior.

South African Calculus Bovis: Smooth and shiny exterior.

Indian Calculus Bovis

Indian Calculus Bovis

Video Introduction by Dr. Da Zhen on Traditional Chinese Medicine:

https://youtu.be/UC-VBeGz-Mo

“Calculus Bovis is a disease of the cow. Therefore, cows with calculus are often sick and prone to death. All beasts have calculus, and so do humans when they have jaundice. Because the disease is in the area between the heart and the liver and gallbladder, it congeals into calculus, and thus can treat diseases of the heart, liver, and gallbladder…

According to the History of Song, ‘When Zong Ze was the prefect of Laizhou, officials took Calculus Bovis. Ze said: ‘In spring, there is an epidemic, and cows drink the poison, which congeals into calculus. Now, as the benevolent Qi circulates, cows have no calculus.’ From this, it can be further confirmed that calculus is a cow’s disease.’

《Compendium of Materia Medica, Volume 50 of Beasts, Beasts》 by Li Shizhen, Ming Dynasty

The above passage explains that Calculus Bovis is born from sick cows, and various animals can have it, as can humans. It also explains that the cause and environment of Calculus Bovis are related.

According to the fourth edition of the Taiwan Chinese Medicine Pharmacopoeia, Calculus Bovis (https://reurl.cc/eOv9bM) is the dried gallstone of the bovine animal *Bos taurus domesticus* Gmelin. When slaughtering cattle, if Calculus Bovis is found, the bile is filtered out, the Calculus Bovis is extracted, the outer membrane is removed, and it is air-dried. It is commonly known as “Natural Calculus Bovis.” The bilirubin content in this product shall not be less than 25.0%. “Natural Calculus Bovis” is mainly produced in Hebei, Xinjiang, Sichuan, Qinghai, Tibet, Henan, Gansu, Shaanxi, and other places. It is also found in places around the world such as India, Canada, Argentina, and Uruguay. In Taiwan, the common Calculus Bovis found in the market mainly comes from South American countries. Since the ox belongs to the “Chou” (丑) hour in the twelve earthly branches, it is also called “Chouhuang” (醜黃) or “Choubao” (醜寶). Because it is mainly derived from gallstones in the liver and gallbladder, it is also called “Danhuang” (膽黃) or “Ganhuan” (肝黃). It is usually best when it is intact, brownish-yellow, brittle in texture, with clear and fine layered patterns on the cross-section. Natural Calculus Bovis comes from gallstones in cattle, and healthy cattle generally cannot produce it. A survey conducted in Japan in the 1970s found that only about two in a thousand cattle nationwide could produce Calculus Bovis, and in China, only six to twenty in a thousand cattle could obtain it. This shows its rarity, which is why there are now different production methods such as “Artificial Calculus Bovis” or “Cultured Calculus Bovis.” “Artificial Calculus Bovis” is quantitatively analyzed by Japanese scholars based on the components of natural Calculus Bovis. It was found that its main components include bilirubin, cholesterol, bile salts, lecithin, fat, and some inorganic salts containing calcium, magnesium, and iron. These are mixed in the same proportions. “Cultured Calculus Bovis” involves implanting an artificial core into the cow’s gallbladder, then controlling the cow’s physiological structure to induce gallstone lesions, and finally surgically extracting the Calculus Bovis. From the above, it can be seen that their sources and manufacturing methods are different. The Taiwan Chinese Medicine Pharmacopoeia describes its taste as sweet and bitter, with a cool nature, and it affects the heart and liver meridians. Its main functions are to clear the heart and resolve phlegm, open orifices and awaken the spirit, clear the liver and detoxify, and extinguish wind and stop spasms. This shows the special nature of its medicinal effects.

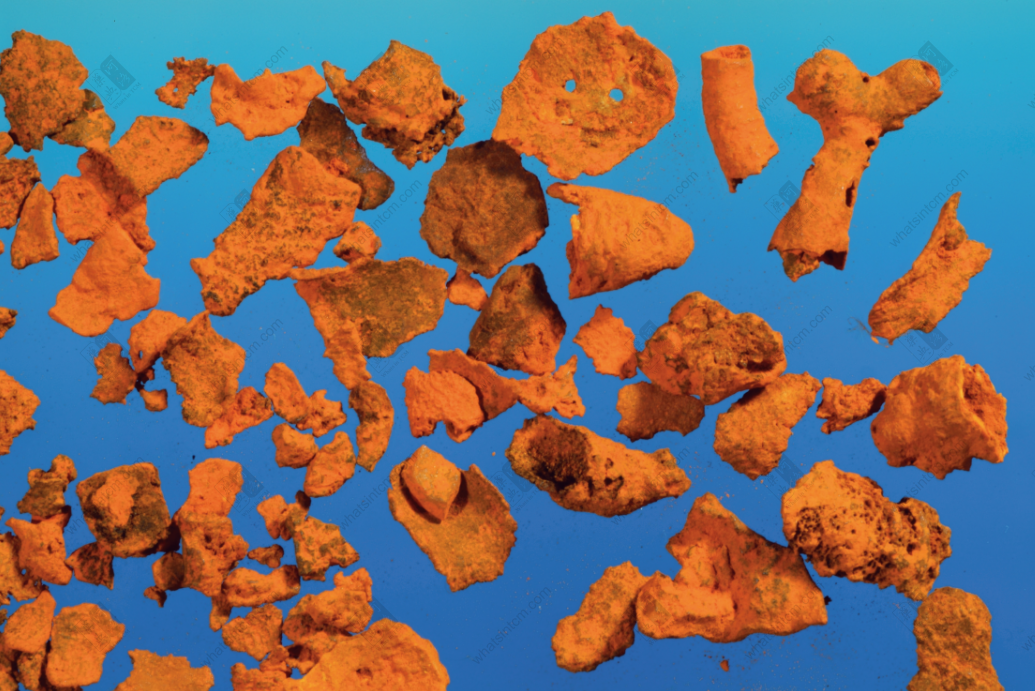

Because Calculus Bovis is difficult to obtain and is a precious medicinal material, it has been very difficult to obtain throughout the years. The Tang Dynasty’s “Xin Xiu Ben Cao, Volume 15, Beasts Above” records: “Nowadays, many people obtain it from the gallbladder. It is mostly produced in Liang and Yi. One piece, the size of a chicken’s yolk, overlaps. There is nothing more precious in medicine. One piece costs two or three fen, and good ones are worth five or six thousand to ten thousand. Common people often fake it, and it looks very similar. Only if it can be rubbed on the fingernail and doesn’t come off is it real.” This shows that the quantity was very small even in the Tang Dynasty. Because of its high price and the existence of fakes, the method of identification is that Calculus Bovis liquid can dye fingernails yellow, and it is difficult to remove, which is now called “挂甲” (guà jiǎ, nail hanging). Today’s common Calculus Bovis can be divided into egg-shaped Calculus Bovis, which is yellow or brownish-yellow, fine and slightly lustrous. Some have a black, shiny thin film on the surface, commonly known as “Wujinyi” (烏金衣). The surface is rough, with warty protrusions, or crack lines. The cross-section is yellow, and dense and fine concentric ring patterns are usually visible, some with a white center. It has a clear fragrance when smelled, a slightly bitter and then sweet taste with a cooling sensation, and is easily crushed and does not stick to the teeth when chewed. Another type is pipe-shaped Calculus Bovis, which is mostly short tube-shaped or broken into pieces of various sizes. The surface is brownish-red, rough, with raised small bumps, and also has obvious cracks. The center of the cross-section is blackish-brown or hollow, with layered patterns on the periphery, mostly brown. Artificial Calculus Bovis is mostly processed from bile acids, bilirubin, and added inorganic salts from cattle or pig bile. It is mostly earthy yellow, loose powder, formed into irregular spheres or squares. Its aqueous solution can also “hang nails.” It has a faint fragrance and a slightly fishy odor when smelled, and a slightly bitter taste but no cooling sensation in the mouth. In addition, “Cultured Calculus Bovis” is usually in irregular pieces or powder form, with a brownish-yellow or yellowish-brown color. The texture is relatively loose, with a small amount of grayish-white loose material and black hard lumps interspersed. It has a slightly fishy odor when smelled, and a slightly bitter and then sweet taste with a cooling sensation.

In the market, gallstones from the gallbladders of dromedary camels (family Camelidae) can also be found as camel calculus. They are usually large, rough in texture, dull, and taste salty without a cooling sensation. In addition, gallstones from the gallbladders of black bears (family Ursidae) are bear bile calculus. The cross-section has no obvious layered pattern and no bear bile odor. There are also dried gallstones from the gallbladders, bile ducts, and liver ducts of pigs (family Suidae). They are oval in shape and vary in size. The surface is yellowish-white, grayish-yellow, or reddish-yellow. Some have a knot in the center. They have a slightly fishy odor when smelled, a slightly bitter and slightly cool taste, and do not exhibit the “nail hanging” phenomenon when moistened. In addition, there are processed products made from Coptis chinensis, rhubarb, and turmeric powder, mixed with egg yolk, bile, and other substances. They are dull, heavy, have a brownish-red cross-section, and no layered pattern. They have no clear fragrance when smelled, taste bitter, stick to the teeth when chewed, and when moistened with water, the color is easily rubbed off the fingernail, thus showing no “nail penetration” phenomenon. Finally, there are processed products made from potato tubers, which are usually blackish-brown on the surface, rough, and cracked. The cross-section has processed concentric ring patterns. They have a slightly fishy odor when smelled and do not exhibit the “nail hanging” phenomenon. Under a microscope, a large number of starch granules can be seen. From the above, it can be seen that the simplest way to identify Calculus Bovis is to first look at the texture: it should be brittle and easily broken, and powder should be easily scraped off with a fingernail. Secondly, look at the layered pattern: it needs to be cut open to see. Calculus Bovis is composed of numerous fine layered patterns from the outside to the inside. Each layer is very thin, and the layers are dense and clear. There are very fine yellow lines between each layer, and a black line every few layers. Thirdly, look at “nail hanging”: rubbing Calculus Bovis on a wet fingernail a few times will leave a yellow mark. After about 5 seconds, when the nail is dry, the yellow mark cannot be rubbed off or washed off, which is an important identification item. Finally, features such as “Wujinyi,” the smell when smelled, and the taste when tasted are also important identification points.

Calculus Bovis is a noble medicinal material, so special care should be taken when purchasing. The Taiwanese government authorities have set limits for heavy metals such as arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead, as well as for sulfur dioxide in the pharmacopoeia, so the public can use it with confidence. Jingniu Calculus Bovis

Jingniu Calculus Bovis

Calculus Bovis Tablets

Calculus Bovis Tablets

Guan Huang (Pipe-shaped Calculus Bovis)

Guan Huang (Pipe-shaped Calculus Bovis)

Artificial Calculus Bovis

Artificial Calculus Bovis

Close-up of Artificial Calculus Bovis

Close-up of Artificial Calculus Bovis

【Image provided by】Professor Chang Xian-zhe, “Illustrated Guide to Authentic Medicinal Materials” https://whatsintcm.com